Observations on China

August 2008

Randall Lucas

This blog post, adapted from a letter to friends and colleagues, summarizes my observations from a recent trip to Beijing, Shanghai, and some smaller cities in between, during three weeks in August, 2008 (coinciding with, but not focused on, the Summer Olympics).

While no short trip or short document could hope to capture much of this vast country and ancient civilization, I certainly felt I learned quite a lot. My target audience is the Western thinker who has not (recently) visited China; old hands at Sinology are asked to indulge me some basic explanations in parts.

Originally composed at Seattle, Wash., 25 August 2008.

I am dividing my observations into the following broad categories:

– Labor

– Sharp Edges

– Maintenance

– Content

– Health

– Sex

– Law and Government

– Intellectual Property

– Video

– Service

– Salesmanship

– Cargo Cult

—

– Labor

Every Western observation of China must begin with the sheer quantity of humanity. In fact, this great number is not apparent in the way one might find most obvious (on the streets of the cities). Nowhere in Beijing were the streets anywhere near as crowded as, say, a New York shopping street in December. However, this may be because of the government’s Olympic preprations, which, rumor holds, caused all of the construction workers, laid-off and gypsie cabbies, and “aunties” (older cleaning maids) to be sent out of town for the duration.

Rather, the way the relative scarcity or abundance of people is made visible is through the labor market. And the shocking discovery is that /labor is essentially free in China./ The cost of hiring a full-time employee is less than what we would consider, in the West, the mere “overhead” of keeping an employee (taxes, insurance, etc.). Consider the following examples:

A tourist-targeted tailor’s shop offers to add French cuffs to a shirt or working buttonholes to a suit coat for no extra cost. It’s as though the labor involved in sewing is just a loss leader to get the fabric sold.

Each floor of a hotel, each car of a train, and damn near each table at a restaurant has a fuwuyuan, or attendant, serving just that floor or car or table. This is in addition to the normal complement of staff that you would expect (bellmen, clerks, conductors, waiters, etc.).

Foot massage is a ubiquitous creature comfort, and is 40-100 RMB ($6-15 US) for an hour (likely including tea and other consumables) even in the large cities.

Gas costs over 6 RMB a liter, almost $3.40 a gallon, and yet the taxi fare in Beijing is less than 50c per mile. The cabs are either old shitboxes or, surprisingly, many newer Jettas and Hyundais. When you consider that gas and capital costs are nearly the same as for a U.S. cab, the cost of labor almost disappears in the numbers.

Instead of coinboxes, buses have a ticket-seller on board to make change and shepherd passengers.

A result of having such a huge number of people is how you relate to them. My take on the “sea of humanity” effect is that it leads to a binary view of others. You are either Somebody (a friend, a colleague, a customer), or Nobody At All. If you are Somebody (and you can become Somebody through just the briefest exchange or introduction), you will be extended every courtesy. If you are Nobody At All, then expect to be ignored, cut in front of (in line), dismissed with an indecipherable grunt, and almost literally spat upon. It seems rude, but it’s a fairly effective way to run a civilization of a billion and a half souls.

Finally, it is worth noting that even with all these people, on the ground, China still operates at human scale. For example, we bumped into a (Chinese) girl at one tourist site two days after we’d briefly spoken at another, and recognized each other. There are not so many people that these sorts of things can’t happen.

– Sharp Edges

Things in China have sharp edges. Don’t want to fall off the edge of that stone stairway (sans handrail)? Well, don’t walk next to the edge. Don’t want to break an axle driving down a main urban street? Well, don’t drive over that open manhole.

2- and 3-star hotel rooms may or may not have a smoke detector, but will definitely have burn marks all over every tabletop and counter surface from where forgotten cigarettes burned themselves out, thankfully without incident.

I still haven’t figured out what it is the taxi drivers all say when you start to reach for the nonexistent or nonfunctional seat belts in back, but it’s on the order of “give it up.” (Tip: the front passenger “suicide seat” might be a better deal, as its belt more often works.) Beltless cabs comprise 80-90% of the total.

Seatbelts: a fantasia

Traffic itself is a royal flying three-ring clusterfuck with crossed palms. No, it’s nowhere near as interesting as videos you may have seen of bike and motorbike armadas playing chicken with trucks in faraway Asian cities. There do exist controlled intersections, although I’ve seen every category of vehicle, from rusty trike to posh bus, blast full speed through red lights. And the number of truly outrageous specimens, donkey-drawn carts or rickshaws piled high with crates of live chickens, etc., is minimal. But shenanigans like steadily pushing through a left turn against four lanes of oncoming traffic, straddling lanes on the major ring roads, or just plain driving into oncoming traffic for a brief while, are all to be expected from cabbies if not everyone. I recommend dosing your anxiolytic of choice before your first day of cab rides.

Amazingly, I saw only one wrecked car the whole time, although I was close enough to hear and smell the rubber of some squealing near-misses.

Lots of folks wear flip-flops everywhere, despite the ubiquitous presence of shit (by which I mean not junk, but actual turds of unknown provenance). Nails and such are fairly common, although broken glass gets swept up quickly by ubiquitous attendants (see “Labor” above).

If you eat enough, and interesting enough, food, you will eventually be served things that you might choke on (bones, shells, inedible bits, etc.).

The glib, and not a little racist, take on all of this is that with so many people, individuals’ lives and safety count for less. Whether or not this is true, I don’t think it has explanatory power.

My theory is that this state of affairs is the result of limited civil remedies against businesses and the sovereign. If you effectively can’t be sued or voted from office, then why fix, clean up, or make safe your restaurant, shop, or city?

Safety first!

– Maintenance

Maintenance of capital assets is simply not a natural follow-on to their acquisition in the way we think of as a best practice in the West.

Of course, things are created and built in China very competently and often on a grandiose scale — think of the Bird’s Nest stadium or the Water Cube for the 2008 Olympics. But I believe that within five years, these gems, if still standing, will have fallen into a shameful disrepair (beyond the norm for disused trophies of expos and games long past, like that weird World’s Fair thingy in Knoxville). This is because nothing, it seems, gets maintained in China.

My first ten nights were spent in a posh apartment in a high-rise built in the last several years by a Hong Kong developer (your hint of this is when the internal signage is all in traditional characters). Covered garage under a fountain and lawn; legions of starched-shirt, polite security guards; marble, steel, flat-screen TVs and all that. We towered above the neighboring tenements. But despite all of this, there were subtle hints that something was amiss. A sheet-metal sign near the private tennis courts was bent at the corner into a menacing protrusion. Some of the flagstones were broken, others wobbly. The elevators were intermittently functional.

The residents of this high-rise were expats (one gal working for the U.S. Army was dropping $4000 of your tax dollars monthly on a two-bedroom) or Chinese upper-class folks: surgeons, bankers, and the children of the wealthy. So, while this building was hardly the very most upscale in Beijing, it was no slouch even by U.S. (cost) standards. Yet the maintenance of the facility lagged well below what Americans might expect from, say, a well-run Holiday Inn franchise.

Paradoxically, it felt as though we were in a place where capital (initial building cost) was “cheap” while operating expense (mainly labor) was “expensive.” Of course (see “Labor” above), labor opex is nearly free, while capital (though the issue is complex and nonmonotonic) is constrained. This makes me think that the problem is probably a mix of management culture and accounting practice.

Other examples of maintenance issues are visible at hotels which have been open more than a few years. As the Lonely Planet “China” guide opined, many hotels are “manifestly” one star lower than their ostensible rating after having been open a while.

Grand Hotel, Petite Slippers

Finally, I want to make a couple of observations about maintenance of historical sites. Specifically, on Tai Shan, the holiest mountain of Daoism, there are numerous shrines and temples up and down the slope. They are often in ill-repair from an infrastructure-maintenance point of view, but this is not because they are in any way being historically preserved for “authenticity.” Many of them bear plaques indicating their age, but a curious pattern emerges. The typical plaque says something like:

“The Temple of the Holy She-Wolf has been here since antiquity, but has been rebuilt many times since 1650.”

Is that the same temple that was there in 1650? Or the same as was there in antiquity? The writer of the plaque seems to imply that it is the same, merely rebuilt. Or perhaps it doesn’t matter that it is no longer the same; perhaps there is an Eastern philosophical outlook at play that suggests we overlook the artificiality of the new vs. old distinction.

But if that sounds hokey to you, it does to me, as well. I think a more likely suggestion is that since some parts of China are so very old, and since history gets measured there in dynasties instead of decades, the “oldness” of a 1970-rebuilt temple vs. an 1890-rebuilt temple vs. a 1770 rebuilt temple vs. a 1650 rebuilt one is all about the same — on the order of “not that old.” I also suggest that a sense of permanence accompanies this idea of longevity, so that any urgency is removed from the need to keep things just so. Combine that with a lackadaisical approach to routine maintenance, and it starts to make sense to just rebuild the Temple of the Holy She-Wolf every several decades after it’s crumbled past some unusable point.

– Content

China is dying for content. To a first approximation, all content in China sucks.

Television is horrendous. CCTV (state television) controls several channels, and apart from heavily censored news (with Mao’s portrait over the Forbidden City behind the anchors) and Olympic sports, the content was:

Kung-Fu Movies

Soap Operas

Bland Music Shows

But mostly, Kung-Fu. I know it sounds like a bad joke, but it’s not. At any given time you can turn on the TV in Beijing and find at least two channels with some guy in a ponytail kicking some guy in pajamas. And we’re not talking Jackie Chan or Bruce Lee, export quality stuff — this is mainland Chinese knockoff, crappy effects, no athleticism, martial arts mush.

I managed to flip through the 20 or so channels available about once a day. The only imported Western content I saw was an overdubbed episode of “Growing Pains,” the 1980s sitcom.

(In non-broadcast media [e.g. DVD or VCD] you can get dubiously licit copies of Hong Kong movies, which are usually still pretty high on the Kung-Fu and the violence but have something approaching plot, cinematography, and acting to bolster it. And, of course, pirated Western movies are around on DVD, although the Olympic cleanup effort swept most of this into back alley shops.)

In print media, I am told you can get a copy of the NY Times or the Wall Street Journal in a five-star hotel. However, I never once saw one. Not in a hotel, not in a newsstand, and not even in the largest foreign-language bookstore on Beijing’s main shopping drag.

China wants content. Adores content. Needs content. And by “content,” I mean both the longer-form stuff — albums, movies, TV shows, songs — that we typically think of, but also the short-form, non-media content that is embedded in products and the built environment, like brands and design.

Look at kids walking down the street. They want content on their shirt so badly that they wear nonsensical, misspelled knockoffs of Western logos, slogans, and graphics. Half the kids in the Internet cafes (wang-bas) are watching video-on-demand.

But there are two totalitarian forces standing in the way of the Chinese getting content: the Chinese government, and Rightsholders.

The Chinese government does not want a populace aroused (in either sense; see “Sex” below) by uncontrolled foreign content. Make no mistake: this is naked fear on the part of the government. But, they control the outlets and the press, so in a move of simple genius, they just don’t allow any uncensored content.

Rightsholders, those rent-seekers who find themselves quasi-legally entitled, in the West at least, to a monopoly on the use of certain information, are just as scared. Their fear is just as blind and just as destructive; for more, see “Intellectual Property” below.

Maybe China has spurious DMCA abuse, too?

– Health

China is a ticking time bomb of public health. Bird flu or SARS are red herrings. The dominating effects over the next 20 years will be chronic lifestyle issues.

Smoking in China is where it was in the West at midcentury, acceptable (and actually done) literally everywhere I went except for inside airplanes and train cars. Restaurants, taxis, Internet wang-bas, you name it. This would not be such a shocker, I admit, if the entire First World hadn’t made a jihad against tobacco its major accomplishment over the last ten years (with even iconically fumigaed French restaurants and Irish bars banning smoking). But it seems very unlikely that this trend will catch on in China (although trends are propagated in odd ways; see “Law and Government” below).

Deep fried everything is more ubiquitous, in some cuisines, than in a Deep Southern lunch counter. In those cuisines that don’t subscribe to the fry-everything model, another lurking danger is the taste for pure animal fat. The costlier a piece of pork is, the more likely it is that it’s got a half-inch thick fat-cap slow cooked and carmelized on top of it. (The first three such morsels you eat will overwhelm you with goodness, melting like a cross between fine smoked slab bacon and cotton-candy in your mouth. But then you realize that there remain twenty more bites on your plate, and the thought of eating a half-pound of suet sobers you up quickly.)

American bobos and self-anointed gourmands who get high on “authenticity” (see also “Intellectual Property” below) will be glad to hear that yes, your local “Jade Garden Pagoda” (or whatever) take-out place is doing it all wrong, and that all that soy and oyster sauce, must not be Truly How It Is Done. But foodies, hippies, and cardiologists alike would be aghast at how much salt, sugar, MSG, and God Knows What Else does “authentically” make it into the food. Drenched in sugary sauces, salted to the extreme, and systematically selected for fattiness describes just about everything besides staples and vegetables.

People (except those who eat only staples and vegetables) are getting fat in China, and it’s going to get worse. The standard Beijing or Shanghai adult male summer uniform of short-sleeve shirt tucked into navy blue polyester pants with some kind of plastic loafers, is not complete without a modest (by American standards) but growing paunch and a phlegm-hacking cough.

Booze flows freely everywhere, and beer is the beverage of choice to accompany meals. (Good damn luck getting a nice glass of red wine outside of a truly upscale restaurant!)

In Beijing and Shanghai at least, the bicycle is no longer ubiquitous. I saw more bicycles (parked) than electric bikes, but the majority of vehicles actually being ridden around were powered (electrical or tiny motors).

Bikes and mopeds: you tell me how folks are getting around

There exist gyms and health clubs, but in nothing like a proportional amount to the population.

– Sex

Maybe the health and wellness industry is stunted because one of its key drivers is completely squelched. Chinese aren’t yet whipped into a neurotic frenzy over body image and attractiveness, because there is essentially no sex in the media in China.

By no sex, I mean at any level. TV and movie content may be romantic but is largely chaste. The only “bikini” level body exposure in any medium I saw was during Olympic beach volleyball broadcasts. And rap music video-style booty shaking, Cosmo-style cleavage-showing magazine covers, or outright porno? Forget it. It’s just not there.

That’s not to say that there’s no sex industry in China. It’s just run in a complete mirror image of the way an American might expect: prostitution is ubiquitous and rampant, but harmless looking is completely impossible. (Gentle reader, trust that I had only your curiosity in mind during my research; suffice to say my conscience remains clean, yea though my mind be incorrigibly dirty.)

There exist “sex shops” in the major cities, but, curiously, they sell only “appliances” and not pornography.

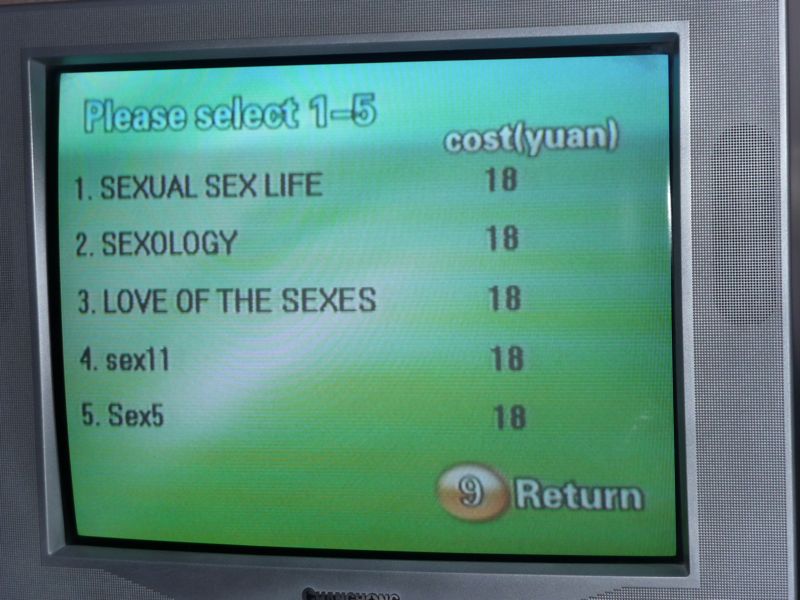

My Shanghai (a more Westernized and racier city by far) hotel ostensibly had adult video-on-demand on the TVs in the room.

Now those are some enticing titles

Massage parlors are commonplace and, with obvious hookerific exceptions, completely legitimate (or rather, I should say it is possible to get a completely legitimate foot rub there). 45 minutes into the hour long foot massage, though, the inquiries begin: do you have a taitai or a nupengyou (a wife or a girlfriend)? Locals confirm that it is nearly always possible to negotiate extra services, even at these “legitimate” establishments.

Also fairly blatant is the pimp’s street come-on, common on tourist streets after dark: “Hello hello my friend, you like lady?”

Despite the fact that you’re never a kilometer from a negotiably naughty massage joint, there are no nudie or strip clubs at all. A Beijing Hooter’s franchise is as close as you can get.

I find it hard to believe that market demand is what shapes this skewed-to-extremes adult entertainment industry; after all, one would expect that increasing social opporobrium on the scale from Hooter’s to hookers would suppress incidence. The opposite is true of market offerings in China. Which is almost certainly the result of government policy.

– Law and Government

The law and the government (very nearly one and the same) in China use a bizarre mix of laissez-faire and complete thuggery to distort the hell out of various markets at the whim of the relevant officials.

Most of you have probably heard about the dramatic measures the government took to clean the air in time for the Olympics: unilateral shutdown of nearby factories, car rationing by license number, and even cloud-seeding to induce cleansing rains. Did you also know that the leftmost lane on every expressway around Beijing was repainted with Olympic rings, for the exclusive use of credentialed Olympic vehicles? Or that every single taxi driver in Beijing was spruced up with a collared shirt and tie, at risk of a 200 RMB fine, for the games’ duration?

These measures sound slightly wacky, and, at least to you collectivist Seattle eco-hippie readers unconcerned with factories’ positive contributions or cabbies’ sartorial discretion, mostly harmless. (The anti-spitting propaganda campaign, for example, was definitely a plus.)

But an example of something more troubling is the clean-up approach to the crime on Beijing’s premier bar street, the Sanlitun district. Like any nightlife area, it had an underground economy, and as is common everywhere, foreign (in this case, North African) gangs had mastered the distribution chain for the relevant goods. The rumor we heard in hushed tones from Sanlitun regulars, as they pointed out the absence of nearly all black folks from the district, was that two weeks before the Olympics, the police simply gave the bum’s rush to any blacks they found in Sanlitun. The cops logic was brutal but effective, in the Chinese style: some North Africans are known to be dealing in Sanlitun, so let’s drive anyone who looks vaugely like that out of the district. Problem solved, sort of, and quite messily, in that way that the Chinese government solves problems.

Another “solution” is ubiquitous surveillance. Tourists enjoying the Summer Palace (which, by the way, puts Versailles to shame both in grandeur and in tastelessness) will see staring back at them, among the odd-numbered gargoyles atop the pagoda roofs, closed-circuit TV cameras in steel housings. (In a weird echo of Orwell’s telescreen, the name of the Chinese state TV broadcasting monopoly mirrors back the name of the surveillance cameras: CCTV.)

Cops are everywhere in China, though they kind of look like rejects from the third string of the little league minor team — skinny kids in ill-fitting green uniforms — or else slightly more swaggering versions of the universal Chinese adult male (avec paunch, emphysematic hack, and navy blue polyester). Nobody seems to have a gun, except for the occasional hardcore ninja team that sweeps through transit hubs with machine guns and full armor.

The operation of the cops on the ground is a sort of mirror of the operation of the government at large. In Qingdao, on the boardwalk to the little pagoda in the harbor (see your nearest Tsingtao beer bottle label for an illustration), hawkers selling seashells, carved bone combs, and similar items do a brisk business selling to the (Chinese) tourist throng.

Qingdao vendors (crouched/seated on the dock) before the cops.

As I walked back toward the shore from the end of the pier, though, I noticed the vendors getting all a-twitter and standing up from their crouches. A cop car was slowly rolling down the pier. As the car got about 10 meters away from each vendor (camouflaged by the crowds), each vendor rolled up his seashells and tossed them into the sea, some jumping to follow their package into the water. Once the cops had made their way down to the end, they stopped, turned around, and headed back — and just exactly opposite the way they disappeared, the frogman vendors and their goods reappeared back in their original places, a bit damp but back to business. There was no secret as to exactly what each party was doing, but as long as the cops didn’t see the vendors actually in flagrante delicto, everything was kosher.

Where'd they go? (Hint: into the drink)

(Alas, I was too scaredy-cat to photograph the cops themselves.) The Qingdao seashell sellers exemplify the approach of small entrepreneurs to the law — scrupulous compliance (or at least invisibility) when the eye of the authorities is turned, and business as usual when it looks away.

The government does not always rely on the formula of muscle plus surveillance, however. Ingenious little incentives are sometimes used, too.

In restaurants (here as everywhere), there is a strong incentive not to ring up cash-paying customers properly, in order to skim tax-free into either employees’, managers’, or owners’ pockets. This problem is compounded by the fact that everyone pays cash and restaurants rarely use computerized tills. In order to get restaurants properly to account for charges, though, the tax authorities turn to the customers for help. Asking for a fa piao (receipt) with a government inventory control number on it (and a carbon copy to the revenuer) gives you, the diner, the chance to win 10 RMB by scratching off a lottery ticket-like box. (As far as we could tell, this is the only “gambling” permitted north of Macau!) Your waiter will grumble and pretend not to understand you, but if you repeat “fa piao” enough, he’ll eventually bring you the ticket, fulfilling the tax authority’s purpose.

– Intellectual “Property”

Here in the West we have an authority that has very successfully corrupted our lawmakers into granting it “taxation” rights over the public: the Walt Disney Corporation. Although our Constitution specifically and unambiguously requires that copyrights be for “limited Times,” Disney and its friends among the copyright holders (the Rightsholders) have managed to turn it into an effectively perpetual rent. This is, of course, so remarkably lucrative that it inspires phenomenal amounts of both fear and greed.

When the Rightsholders think of any place, medium, or system in which they lack the ability to strangle free speech with their ill-gotten legal cudgel, their immediate conclusion is: “If we let our increasingly digitized content into [place], our rights will be violated and our content will be instantly uploaded with bitwise fidelity into a giant cloud of sharing! Therefore, blockade and stonewall, and protect our precious rents!”

Think of the RIAA and MPAA reacting to VCRs, Napster, just about every home computer peripheral that can write data, Internet music distribution, etc. and you can see this pattern repeated over and over.

I am fairly certain that the Rightsholders have this view toward China, as well. (For much of Hollywood’s sex-drenched pulp, the blockade is unnecessary, as the government would censor it anyhow; see “Sex” above.) This is not due merely to fear that the content might be redistributed back to their home markets digitally, but it is also due to greed at the prospect of eventually selling billions of copies of “Steamboat Willie” or “Eagles Greatest Hits Volume 2” to a pacified middle kingdom.

The more nuanced or subtle (but still conservative business-friendly) view of Intellectual “Property” in the West is that the culture of respect for IP is important to enable R&D and content-producing businesses. This view makes respect for IP part of a climate that permits innovation and entrepreneurship, and ultimately, economic growth.

This binary view of a country’s attitude toward IP — respected or not respected, rights consistently enforced or not enforced — is completely inadequate, however, to understand how IP is viewed and treated in China.

For starters, I hold that IP in the form of branding is hugely respected in China — in the sense of a recognition that branding holds great power and that it is valuable. Look at the rising Chinese-native athletic wear brand, Li Ning. The logo is a clear rip-off of the Nike “swoosh.” The English-language slogan, “anything is possible,” comes straight from Adidas’ Olympic promotional phrase, “impossible is nothing.”

Does that "swoosh" motif look familiar?

Tidy little syllogisms: if "Impossible is Nothing," then ... ?

The power of a brand is clearly respected in China — why else would they want so badly to rip one (or two) off? It is only the ownership and exclusivity that is not respected. The thirst for content is there (see “Content” above), but the willingness to play by the Rightsholders’ rules isn’t.

None of this means, however, that IP has no value. Quite the opposite. The value might be different (including “less”) or it might merely be unlocked or monetized differently. But people are willing to pay for branded goods and content in China.

Two brand- and IP-heavy companies from the West have very clearly figured out the Chinese IP code, in my opinion. The two are very different, though what they’ve learned is largely the same, so I split them apart here.

Microsoft has the perfect approach to China. They know full well that the high-priced software they sell in the West isn’t economical for the vast majority of consumers or even businesses. So, they let sharing (“piracy”) flourish. As a result, Microsoft is the de facto standard for operating systems, despite the government’s nationalist efforts at an Open Source “Red Flag” GNU/Linux distribution. As businesses mature and interoperate with the West, their default choice of Microsoft as a platform, originally free (pirated), will result in later paid installs and flourishing of the proprietary Microsoft ecosystem.

Audi, too, has cracked the code, to some extent. The black Audi A6 is the rough equivalent of the Lincoln town car or the Mercedes S500 sedan in North America and Europe, respectively — the “executive” car or choice. These Audis, however, are by and large not the newest A6s, with the styling one sees in a posh parking lot in the US, nor are they large-engine (4.2L or larger) powerhouses. And perhaps most tellingly, they are almost never Quattro (all-time 4-wheel drive) — the sine qua non of Audi’s branding work in the West (see e.g. “nur fuer Audi” mountain roads). Audi has thrown away the key elements of its Western branding — newest styling, large engine displacement and/or turbo, and Quattro all-wheel drive — in favor of pushing (probably through a shrewd licensing deal) lots of black A6s into the Chinese market. And the result is very favorable; they are the de facto standard in Beijing (especially for the Olympics) and Shanghai for chaufferred luxury sedans.

– Video

My observations on Video are almost an add-on to “Intellectual Property” (above), and certainly share some common themes. Video entertainment and communications are treated much differently in China than in the West, and I think the key difference is in “quality of service.”

In China, video is available. Notice, I don’t say “available to those with 6.0 Mbps download speed” or “available on certain models” or “available for a fee.” I say “available.” And what that means is that, by hook or by crook, video is going to find its way down your uplink.

Asia is home to the Video CD (VCD) format(s), the (crappy) VHS-equivalent digital video smorgasbord. China specifically enjoys a plurality of standards that will squeeze down onto whatever pipe or medium is available. Hotel VOD (Video on Demand) often appears to be VCD or worse. Broadcast and cable TV ranges from the shiniest high-bitrate product (main CCTV) to seriously degraded, distorted and discolored signal from local stations.

In any wang-ba of size, you will see numerous folks plugged in and watching video streaming over the Web. It’s never YouTube, and it’s often washed-out colors with bad quality, but it’s ubiquitous. Somehow (and my vocabulary was insufficient to the task fo figuring out what codecs and methods these were), the Chinese have figured out how to make video a ubiquitous part of their digital experience without handwringing over HD-DVD, bickering over Blue-Ray, or dicking around with DRM.

This parallels the Intellectual Property observations to some extent: worse is better, and getting your stuff out there is the key thing to do. How you do it, and how well you do it, takes a back seat to just getting ‘er done (more or less).

– Service

This eminently practical attitude of just “getting ‘er done (more or less)” has a dark side, however. Doing the bare minimum to get something done is, without a doubt, the default method by which work in China gets accomplished. The notion of “customer service,” or the phrase “above and beyond,” are unknown here.

Ask a ticket agent for a ticket to Qingdao. “Mei you.” (“Don’t have.”) Don’t give up — you asked (implicitly) for a standard fare. What about a sleeper car? “Mei you.” What about hard-class (bench)? “Mei you.” What about first-class sleeper? “San bai yuan.” (“That’ll be 300 bucks, please.”) Ok, thanks, I’ll take that ticket, and fuck you very much for checking the other classes for me.

Unfortunately, that sort of automaton-like response to your requests is very common, especially where the job is more rote, the customers more numerous, or the employee closer to being in the government’s service. This is different, admittedly, only in degree and not in kind, from what you can expect from such employees here in the States, but it is very pronounced in China.

Restaurants, from the slightly-above-average on down (except fast food) will not give you napkins, unless you ask, and those napkins are about the same consistency of high-end toilet paper.

Cab drivers are practically speaking incapable (though more likely, unwilling) of reading, or even orienting themselves on, the most basic of maps (even those marked in Chinese characters). They show remarkable creativity in finding places to drive, but very little initiative in figuring out where you want to go.

This general “I-don’t-give-a-shit” attitude (see “Labor” above) is pervasive but probably explainable with some fairly straightforward analysis. Tipping is unheard of in China, except for those with some Western experience who will try to hustle newly-arrived laowais into leaving them the change from a big bill. Quality Control is simply not something that service industries bother with yet. So without either a bottoms-up or tops-down incentive for improving service, why should anyone care?

– Salesmanship

A little bit more curious is the lack of salesmanship talent in China. Here, incentives should be rather obvious — commission for sales. Indeed, the motivation is quite apparent among hawkers at tourist-facing retail outlets. But everything here gets sold as a commodity — bargained on price — and the notion of selling value to the customer is unknown.

I realize that it’s a bit much to hope a retail clerk to understand “unique selling proposition” or “differentiation” in translation. But the concepts themselves, I am convinced, are not understood by sellers. Conversations with Western-educated businesspeople confirmed that even up the value chain, and for larger and larger deals, the same holds true.

My personal theory is that, in China’s dealings with the West for the last 30 years, the price (labor cost) advantage has been so decisive that the competitive pressures that would otherwise lead to differentiation have been absent. In a sense, the “free money” that the labor cost arbitrage has left on the table has made Chinese business lazy and uncreative about creating value (rather than just capturing the labor cost delta). As a result, skills at differentiating product, selling value, and articulating a selling proposition are still in development.

It should be noted, however, that the concept (or at least the empty word) of “quality” is certainly known and much bandied-about. However, it’s recited in almost a caricature of how you might imagine a Chinese merchant — “very good quality!” excitedly repeated about every object, no matter its obvious shabbiness.

– Cargo Cult

The vendors know that saying something is “quality” is supposed to make somebody buy, or pay a higher price for, an item. But they seem to have no concept about what it is that underlies this notion of “quality.” In effect, they seem to be cargo-culting the notion of quality.

An aside on the idea of a Cargo Cult: briefly, after World War II there remained certain isolated islands that were once used as airstrips but were thereafter abandoned by the militaries. The native inhabitants were found many years later to have created religions and ceremonies mimicking the use of runways, radios, control towers, and ground crews, in hopes of eliciting the “magic” cargo from the skies (and doubtless the high-calorie treats and other Western goods the GI’s doled out). These (possibly apocryphal) natives were said to have created “Cargo Cults,” and the name sticks to this day, especially in the tech industry, as meaning any rote repetition of an action in search of its characteristic response without any understanding of the underlying mechanism of the original process.

Although it may seem to smack of Western arrogance, I can’t shake the feeling that a lot of what goes on in China, and especially a lot of what I have written about above, ends up being reducible to the notion of cargo-culting. Yes, having a clean sheet over the back seat of a taxi is, standing alone, probably a sign of higher quality. But it’s of lower quality when that sheet blocks the seat belts from working. Yes, it’s generally good to have lots of “volunteers” to guide foreigners when you host the Olympics. But putting a tent up and putting polo shirts on the same four old men who would otherwise be squatting on the same street corner, without any training or maps or information or value-add, completely misses the point of having volunteers.

A less culturally-charged way of saying this might be that the Chinese “go through the motions” for a lot of things. But the things I noticed are ones imported from the West, which makes them seem cargo-cult-like.

– Conclusion

Much of the above comes across as critical, which reflects the frustration I felt as my third week in-country approached and I sketched out these notes. I acknowledge that this emotional content would be a weakness of an objective account; however, this is meant to be a thoughtful but subjective and opinionated piece.

I left China without either a great apprehension of the rising hegemon, nor with any sense that our Western advantages will hold past the horizon we today can see. But my perpsective /was/ changed and honed. The measures that one might naively use to measure’s China’s great catch-up — % GDP growth, number of universities per capita, degrees awarded, power plants constructed, durable goods orders — these are all meaningful in their own fashions, but are red herrings when it comes to commensurability with the West. Things like civil institutions, the culture of business, salesmanship, and service, IP regimes, and cultural mores will ultimately mean more than these easily quantifiable (and easily falsifiable) figures.

The experience also has helped highlight for me those cultural and institutional parts of American culture that might otherwise be taken for granted. We must not discount the role of things like R&D, value-based pricing, the emphasis on industrial standards, and individual initiative within large organizations, for the effect they have on our collective wealth and national effectiveness.

All that said, gentle reader, I have only scratched the surface and can’t wait to get back to learn and experience more of the country that is destined to be our greatest trading partner, our greatest military rival, and our greatest source of learning during the next century. This is my account; now, please correct, challenge, and contradict me at will.